Inland Renderings: Ruminations on Queer Reproduction, Agricultural Archives, and Douglas Wright’s Inland

Frances Libeau

INLAND RENDERINGS

Oh God….I hate this fucking country

The grass is so green

The sky is so blue

Baa baa black banks of grass

Have you any fully adjustable shelves and door(s) and cabinets?1

IS THAT AN ORIGINAL?

Consider the sounds of a body, its many voices. Consider many bodies and their many sounds. The sounds of bodies at work, at play, at pleasure, at rest; being born and passing away, grafting and splintering in formations both ancient and ever-new. A humming and continuous stream, consistent only in its relentlessness, “a surge of turbulent information and noise… part of a continuum of vibration that precedes and exceeds the spectrum of audibility… sound claims us.”2 As a teenager, while texting on my Nokia 4410, I heard the tune of my ringtone echoed in the song of the tūī in the back garden.

The human capture and reproduction of sound and image is a way of gesturing at (or hailing to) elements of the world we consider valuable enough to point to and say: stop! look! listen! Reproduction—in the sense of the social, economic, agricultural and cultural (the latter referring to the virtual and material proliferation of media we live amidst, in media res)—is a potent force in service of the colonial capitalist agenda. It is also, as noted by sound studies scholar Marie Thompson, “a central but largely unquestioned concept in sound and music studies, where it is typically used to refer to the capture, mediation, repetition, and distribution of sound via practices and processes of recording.3

I hear cicadas. Summer

Drone

On the DVD menu.

[Did the composer pick this

part? other animal noises–– sheep–

bleats processed sound spectral.

Can a sheep throw its voice?

menu does not scroll well.

graphics glitch– it takes trying three laptops– each older than the last–

to play

what is it the cicadas

are saying?

Hands clap– hocket with heavy

ruminant breath

If I wait long enough will it loop

back?]

The choreographer, dancer, writer and artist Douglas Wright grew up in rural South Auckland in the early 1960s, where “a dancing boy was frowned on with a frown handed down for generations.”4 My father went to the same school as Douglas at the same time, and I feel the weight of Douglas’ words with the inherited tapestry of childhood. A frown handed down for generations. We reproduce in many more ways than one.

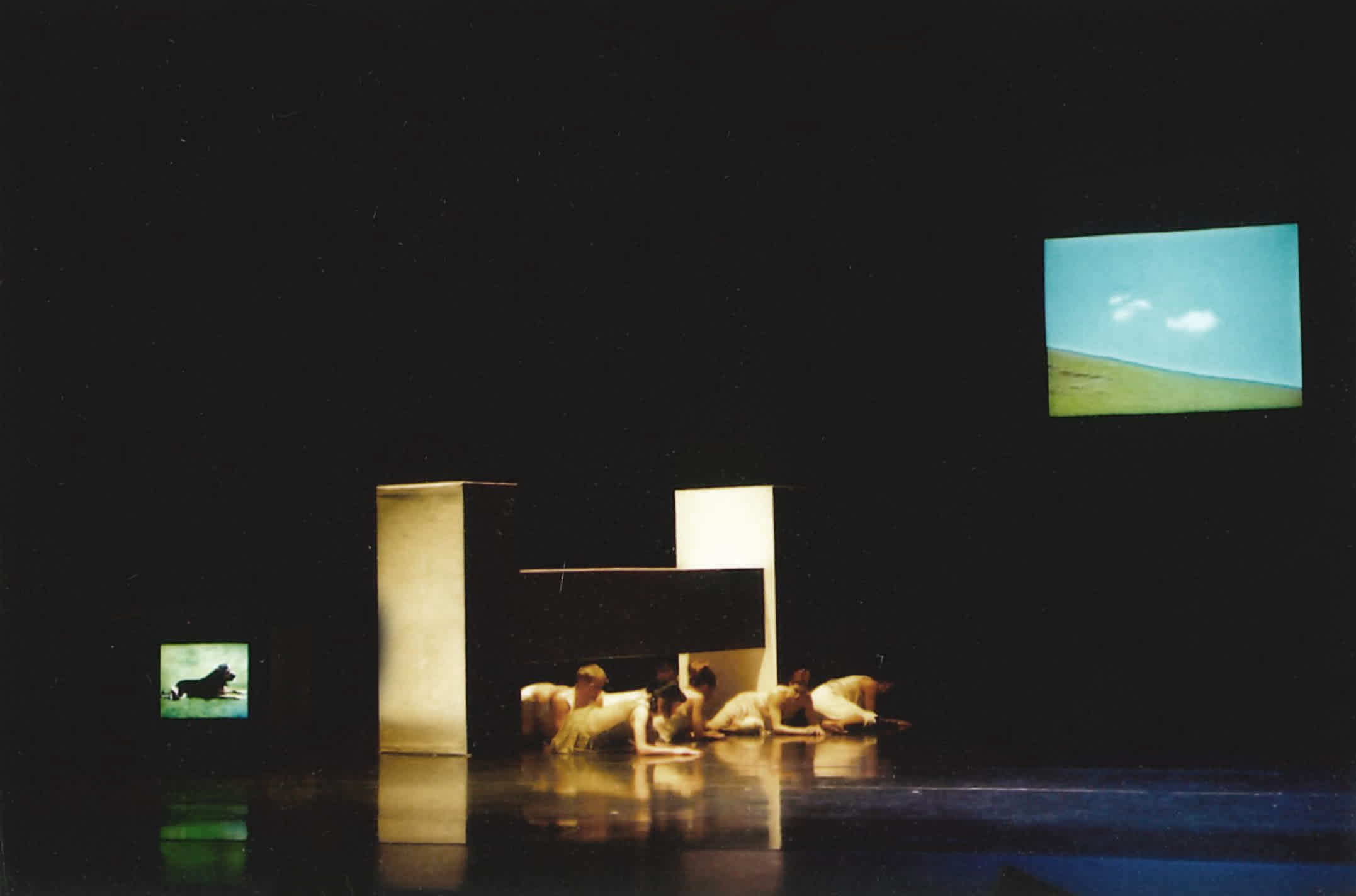

I am watching a DVD reproduction of 2002 work Inland 21 years after its staging in central Auckland. Inland reckons with the landscape, the farm, and the farmed. The performance I’m watching was filmed by Florian Habicht, who would shortly release his own cinematic slice of regional Aotearoa with 2004’s Kaikohe Demolition. The work is choreographed to a score by Juliet Palmer; the music both delicate and immense, a swarm of pipe and string drones freckled with the modulated bleats and beeps of machinated animals.

soundtrack features droning atonal bagpipes and live violin with delays that slap loud

doubling tripling piles heaps of tones droning

slow pitch-bent refrain played multiple times.

do variations occur? Or does it simply sound new as the dance evolves

with each repetition

In a Marxist-feminist context, reproduction involves the gendered labour involved in childbearing and rearing (e.g. childcare, housework). Such labour is relegated to a realm of a lower use-value as compared to that considered as productive labour, i.e. work remunerated with income. If we consider the nuclear family as being a central part in propping up capitalist modes of production, how then, might we consider queer (re)production—that which exists outside of the frame of heteronormative spheres of labour altogether?5 Moreover, how might queer processes of creative (re)production emerge in creative labour, labour ostensibly devalued (and thus gendered) within this capitalist framework?

I think of my dad

a bagpipe player,

when I sent him an album by experimental ex-pat NZ piper David Watson to listen to. He replied saying:

Thanks....I think....

Repetition is not repetition

Jack Halberstam’s suggestion to seek the Other in the dominant dismisses a “nuclear” vision of family (a term associated with essentializing tendencies), rather seeking the queer progeny that irrupts from within and without its seemingly stable bounds. (I have always known this stability to be illusory.) Crucial to queer theory is the notion of resisting easy definition or clear articulation, of exceeding beyond bounds, of slipping through the cracks of the dominant or normative to then rearticulate something else, somewhere else. This is the “wild” or untamed queer, who/which, in heteronormative (reproductive) terms, is a positive failure, unable to subscribe to the “stifling reproductive logics” of heteronormativity.6 This failure is marked as such by its refusal of perceived rules of civility and reproduction:

Heteronormative common sense leads to the equation of success with advancement, capital accumulation, family, ethical conduct, and hope. Other subordinate, queer, or counterhegemonic modes of common sense lead to the association of failure with nonconformity, anticapitalist practices, nonreproductive lifestyles, negativity, and critique.7

This limitless, wild, queer cannot be that which lives in relation to the world from an individualistic, capitalistic, or colonial point of view; it is in constant relationality with networks of difference, power, and privilege. Wildness is not limitlessness, boundarylessness. I wonder where these lines are: for me, for Douglas.

There are yellow lines proliferating

on my screen.

My old laptop’s graphics processor is failing as I watch.

WHAT IS CROOKED CANNOT BECOME STRAIGHT

Lee Edelman proposes this reproductive failure as a space of reclamation for queer people—if we are refusing heteronormativity, then our failure to “naturally” reproduce according to the rules of the nuclear family unit is, by negation, a roaring success. Thus, “a relentless form of negativity” detached from humanist endeavours of meaning-making should be embraced.8 José Esteban Muñoz proposes a more utopian model of failure, a process of “disidentification,” embracing this negativity as a form of queer possibility/potentiality that “scrambles and reconstructs” messages of cultural texts with a vision of futurity.9 In this fashion, the term queer (or quare in both African-American and Irish contexts) used derisively across multiple cultures for hundreds of years, was perversely reclaimed by queer communities in the twentieth century as a descriptor of pride.10 Still, words and signs echo and mutate as languaging-the-world always does, attracting some and alienating others. Queer functions as both methodology and subject, verb and noun in its agitation against the heteronormative. We must, as Mel Y. Chen proposes, “[insist] on queer beyond its affectively neutralized—neutered—senses. What are the possibilities of rejoinder, or revitalization, for this contested term if it still has the capacity to galvanize but also to damage?”11 If queer exists outside the realm of heteronormative logic (and those of its associated hegemonic structures of capitalism and colonisation), it is a space to seize for disorderly creativity, which Halberstam proposes, must embrace monstrous reproduction in order to remain relevant:

Queer theory after nature necessarily comes down on the side of chaos… and in this way, it stays monstrous. If queer theory refuses the monstrous and the dark, it threatens to reproduce orders of knowledge that, like the closet, mark freedom as an accessible space beyond secrecy…12

To look away from, to refuse that which is considered according to a normative socially metric as monstrous, shameful, difficult, is to foster another, ironic form of reproduction—trauma around that very thing. Maybe queerness is a way for reproduction of the so-called-monstrous to be potent, beautiful and animal. “Perhaps the fluttering white moth laid its eggs in me, and my dancing was a kind of hatching,” wonders Douglas.13

A TV set is wheeled across the stage, lead by a walker pulling it by a rope.

The screen plays a moving image of a dog. A dog is walking on this screen I watch.

An image of a dog, moving. A moving image of a dog, on a screen, moving.

What is it to walk

an image of a dog? A

cacophony of dog

whistles

echo loudly.

I can’t see anything for ages, the screen is a dark blur.

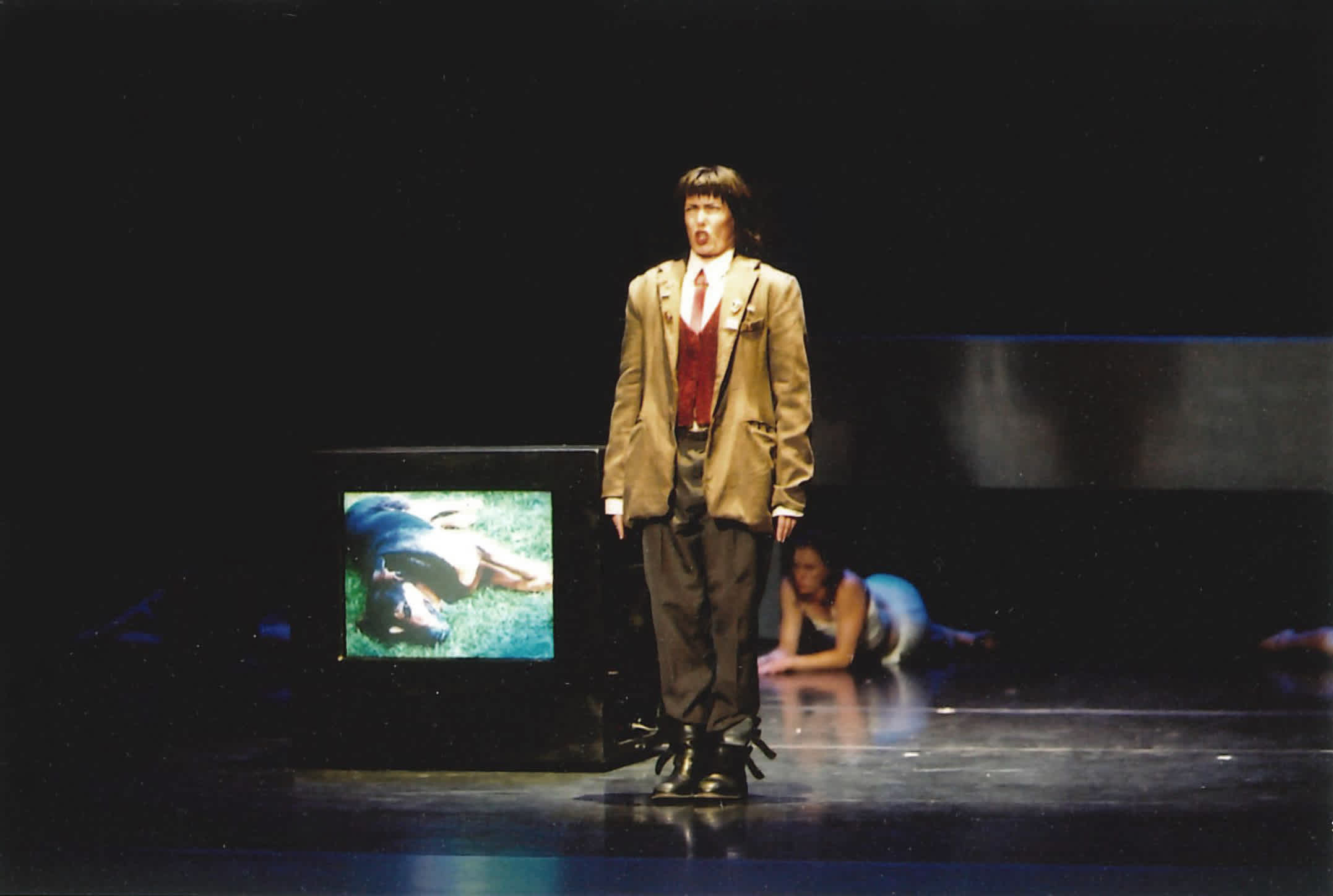

A voice – The Farmer’s – voice calls

In the dark

ANGUS

Stepping into the light we see

The Farmer is a Drag king

NATURE, ENTER ME

Queer bodies have long been interrogated on the grounds of their perceived unnaturalness, the difficulty of queer reproduction along heteronormative lines part of the drive against queer relationships. This impotence is read as an unnatural deviation from a “natural” biological order of society, a rich irony here being that nature-at-large is replete with queer sex and reproduction. The controlled reproduction, exploitation of reproductive organs and processing of animal by-products that takes place in industrialised agricultural farming carries an echo of the perceived “unnaturalness” of queer relationships and a sinister biopolitical agenda—one needs only to scratch at the surface of Dr. Truby King’s Plunket politics to see the eugenicist, anti-queer rhetoric around reproduction that has dominated thinking in Aotearoa for generations. This raises questions around the heteronormative comparison (if not equating) of queerness and animality: as the queer body and impotent (therefore improper) queer desire is not capable of “natural” reproduction, are they incapable of fulfilling the most essential human function, that of procreation? If said queer body is not fulfilling this most “essential” human function, this perceived “naturalness” is called into question—and the queer body is rendered deviant and monstrous, a “bad” animal.

Pipe ++ fiddle drones,

birds

Slices of farmland

[]---[]

fenceposts scaled up 1000X

Abstractions of a landscape painted in lines ~

WHAT IS CROOKED CANNOT BECOME STRAIGHT

The exploitation of animals for their reproductive byproducts is closely tied to a warped yet pervasive notion of “health” in colonial Aotearoa. Ideologies and myths abound around what is natural or unnatural when it comes to bodies, whether human, animal, or synthetic. New Zealand’s colonial image as a bucolic settler’s paradise has been somewhat debunked, yet its primary industry prevails: the farm. Meat and dairy production and processing has long been a primary industry in New Zealand, influencing the formation of colonial national identity, only in recent years coming under scrutiny for its impacts on the environment and indigenous communities. Relationships with animals as meat and dairy products/producers have been “naturalised” to the point that “the most powerful and enduring of our assumptions about animals are those we are most inclined to accept without question, those that have become taken for granted because they serve our interests and investments.”14 An example of this is the milk industry, known for its competitive branding centring on notions of home, family, and health (Fonterra’s 2021 “Taste of Home” campaign for the Anchor brand one of many). Reproduction is core to this industry (breeding for slaughter, milking, artificial insemination), as is the valuing of life (and its usefulness as a reproductive being) according to a colonial hierarchy of animacy. This is tethered to queerness as well as ethnicity, gender and ability through the socially-perceived reproductive dysfunction of queer bodies—”unnatural” being a pervasive, derisive descriptor of LGBTQIA+ relationships.

The pipes and violins do not relent. They sound more and more mechanised and in-organic as time goes on.

Layered, staggered, searing in slow rise glissandos, phasing in and out as the signals

interfere.

I try to draw these glissandos in a stack of sweeping bends. It looks like a narrow set of weather bands; the topography of a very sheer and sudden drop.

∫∫∫∫

Dancers on all fours roll around the floor wearing white woollen vests.

Bag of sheep stomach. Breath of bag.

I think about milk, what it means – nourishing by-product; interspecies ingestion. Millions upon millions of beasts raised and milked for bottled health. The taste of home.

RENDERING

Technologies for the capture and reproduction of sonic and visual media developed in tandem with the industrialisation of agricultural processing and the advent of refrigerated shipping, a technology that would see dairy and meat exports dominate the New Zealand economy for more than 100 years. Refrigerated shipping coincided with the increasingly widespread use of the film camera in the early-to-mid twentieth century. Film stock is itself emulsified in gelatin—and in being so is viscerally dependent on the very processes of animal slaughter that it captures within its frame.

Moving images of agricultural processes were mostly commissioned by the Government’s publicity office with the agenda of drawing attention to the increasing exports of dairy and meat to the United Kingdom and the nationalistic agenda of drawing more colonial settlers and their wealth to New Zealand. Some corporate entities also produced their own long-form advertorials. In these films, the site of agricultural processing—rearing, slaughter and disassembly—becomes, as Nicole Shukin says, an “affective spectacle” through its controlled, highly mediated outward display to the public, spectacularizing “the consumption of animal disassembly… through tours of the vertical abattoir, the material rendering of animal gelatin for film stock.”15

Shukin notes that Henry Ford visited a slaughterhouse and disassembly line in Chicago prior to opening his first Ford factory, and was inspired by the mode of production: “particularly with the speed of the moving overhead chains and hooks that kept animal ‘material’ flowing continuously past laborers consigned to stationary and hyper-repetitive piecework…”16

Douglas’ choreographies frequently cycle through repetitive motifs, spinning in and out of splintering configurations, bodies stuttering between languid fluidity and insect-like fracture. Or is it machine?

Piles of tones again make a topography

Bodies walk backwards with heads bent back

Inverted in an upside down \/

Instructions are incoherent

Shouts become barks

Become whines

Limbs dislocate under blue light

Led by a braid attached to a head

A leash

An umbilical cord?

Reins

Horsehair

Bodies vibrat-

ing

The aforementioned government-commissioned films are often silent, their narratives told through inter-titles. I wonder what sounds might come from these scenes of milking, sheep drenching, smiling children; farmers dressed in white coats like doctors, what a speculative foley might sound like, what voices or impacts might emerge, considering Michel Chion’s note on cinematic sound providing a sensory impression, rather than a mimetic realism.

The sound of sheep being drenched (no sound at all)

(The Foley Of Drowning)

Movement –is just escaping death for a second–

The sound of a digital transcoding error – hissing

A succession (flow/proliferation) of forgettings

Birthing from through hair

A face emerges from behind the curtains

Borne

White as bone

One such agricultural processing film from 1939 (Glimpses of the Frozen Meat Industry in Southland New Zealand)—a silent film—sees a sonic hiss commence about 26 minutes in, during a scene entitled: “The Grozing [sic] Machine Cuts The Inside Flange And The Top Of The Cask.”17 The hiss lasts for precisely half a second and occurs at a frequency of every three seconds and continues on throughout the last four minutes of the film. It is a byproduct of a glitch in archival processing, an invisible disturbance of this document’s functioning as a solely visible piece of media, being altered, warped, mutated through the archival digitisation it has been subjected to. It is an audible glitch, emerging as a spectral voice that is bleary and messy. Sound is not supposed to be bleary, noisy, hissing—a random protest against the clear biopolitical and economic agenda of this document as colonial propaganda. What’s more, as the sound continues, it slowly morphs to gain slightly more of a digital inflection with each repetition—as though the sound itself is evolving; becoming larger, different in timbre—eating itself, or something else. Proliferating from within.

Bird song

Made digital

Mechanical. The voice of it flattened into a crisp resounding

Midi. Midi itself a disembodied, spectral instrument, or rather –

a space upon which an instrument’s sound is played out. A voice itself projected.

From what shaped

Throat?

RUMINATIONS ON AN ARCHIVE

The word ruminant is derived from the Latin rumen, meaning “throat”—the site of both the voice and the breath. It refers to chewing-over-again of partly digested food eaten by so-called ruminants (animals like cattle, sheep and goats). To ruminate is to think, or dwell on a thought repeatedly—as a creature throws up its meal only to chew it over again. The act of digestion is repeated; the meal, in a sense, reanimated in a process of several steps beginning in the throat. Perhaps a replication of a recording of a song sees the singer enter in a similar process. A body of endless echoes.

An archive houses media existing both in and out of time, calling us back to when it was made/captured (first swallowed), yet pulling us into the present (and the process of its capture) by its very preservation, its “liveliness.”18 It is about memory, and the act of remembering: “the recovery of fragments of the past that have become dismembered from the body of the present.”19 As such, the dismemberment of the body means it is a site of phantasms, and hauntings. Engaging with an archive of any kind is akin to speaking with ghosts—human and nonhuman, or listening for their traces. In Douglas’ solo dance Elegy (1993), he holds a lily in his mouth. Is it taking root there, in his body? Or were we always part of the same flesh?

“The past is incomplete and can take on new meanings in the context of its afterlife,” says Catherine Russell of archival media.20 All image is incomplete. Just a fragment of a larger, absent view. This absence is what makes the archive. A total image would obliterate.

The farmer is knitting red thread with oversized needles.

Tools of domestic textile production

become tools

(weapons?)

of shepherding

(capture/restraint?)

Archival capture is a mark of death. Its processes and approaches are fraught with colonial and capitalistic imperatives—closely tied to the archival classificational taxonomy is the imperial animacy scale, developed by Western anthropologists as a mode for classifying the value of a being/object. Yet archival media are not simply vessels or vectors to carry an intended, didactic meaning, but meaning-making objects and processes in themselves that impact our relation to the world and each other. New materialist philosophies have for the last several decades been picking at something that indigenous cosmologies around the world have known for infinitely longer—that everything is animate; that even inanimate matter has energy; has life force (mauri). It is not merely a portal to a different time and place (or its memory), but is itself animate/alive: with a “pulse,” as relayed by Cifor. “Liveliness… is employed to describe a larger vigorousness and vivacity in feeling, activity, intensity, and sensation. Liveliness is understood here to encompass objects and spaces as well as human and non-human bodies.”21

What, then, is it to capture the image of a figure and spin it out into the world in alter-ed/ing reproductions? In Te ao Māori, as eloquently expressed by Natalie Robertson, “photographs [whakaahua] are not dead or lifeless objects but are constantly in a process of becoming form as things with their own agency and interconnected relations in the phenomenological world.”22

Whakaahua means to form, to shape, to transform and to photograph. It also means to form or fashion, therefore implying activation by the hand of a maker. As a noun, whakaahua refers to the thing that has taken or been given form in the photograph, film, illustration, portrait, picture, image or photocopy.23

Each document, each capture, each whakaahua—reproducing and proliferating life.

At some point the stereo audio stutters and

halts on the right side and continues to only play on the left.

The archival artwork seizes on the material thing-ness of media, that which is transformed by temporal and environmental influences to offer a new or altered materiality that speaks to its former state as well as to a present, or potentially even future context. “Death, ruin, and loss remain prominent tropes,” says Russell, “especially with respect to the recovery of celluloid and other time-ravaged media. And yet the experiential, sensual dimensions of reanimated footage, sounds, and images can be visual, dynamic, and very much present.”24 The material and nonhuman forces in each archival object find a new degree of spectral, multi-modal, asynchronous animacy through their archival processing and engagement with spectators.

I jump again between laptop

as the yellow lines obscure the image

Each time I return to the menu and have to manoeuvre the cursor awkwardly to the correct

chapter

How opaque

KEENING

Yoked to all this haunting and refuse is Mark Fisher’s hauntology, drawing on Derrida’s metaphysics of presence which states, in part, that meaning is only stable when anchored to a body. Technologies of making: writing, sounding, imaging—are deferred and consequently absent, spectral and anchored in their own materiality. Parallel to the scratches on celluloid is the crackle of a vinyl recording.

There is no attempt to smooth away the textural discrepancy between the crackly sample and the rest of the recording. If the metaphysics of presence rests on the privileging of speech and the here-and-now, then the metaphysics of crackle is about dyschronia [being out-of-time] and disembodiment. Crackle unsettles the very distinction between surface and depth, between background and foreground. In sonic hauntology, we hear that time is out of joint. The joins are audible in the crackles, the hiss… The surface noise of the sample unsettles the illusion of presence.25

The Farmer crows like a bird, a siren, haunted by a short,

metallic reverb. The stage sounds like a steel bowl.

Fisher considers hauntology as a mode for communicating/remediating the impacts of historical “failures”: trauma, violence and loss. By invoking the past through disembodied reproduction, the future is deferred—perhaps akin to Edelman’s relentless negativity in the context of queer theory. Fisher seizes on the spectral disembodiment and atemporality of media theory that has emerged in the hypermediated twenty-first century. “We live in a time when the past is present, and the present is saturated with the past. Hauntology emerges as a crucial—cultural and political—alternative both to linear history and to postmodernism’s permanent revival. What is mourned most keeningly in hauntological records, it often seems, is the very possibility of loss. With ubiquitous recording and playback, nothing escapes, everything can return.”26

What would it sound like to hear the keening of our own bodies, histories, traumas, griefs—without the stifled logics of the colonial capitalist agenda? What is it to keen? As my Celtic ancestors did through Gaelic folksong? This which I do not yet know how to sound, I hold in my body in a multiplying swarm of ghosts.

THE MUSTER

Working with archival matter is always a process of selection: what is centred and what is pushed out of the frame; their material and evocative histories, what they preserve and what they cast off to other forms of remembering. What is mustered. Muster: from the Latin mōnstrō & French moustrer—to show/point out/indicate (as in demonstrate). This word has the same etymological root as monster.

The Farmer ushers the sheep-dancers (dancer-sheep) into a group

and attempts to

muster them with the red wool

trapping them in their own inanimate offspring

There’s one missing[br]Bother

I’ll have to go

And look for it

In one of his memoirs, which sprawl across time and space in a totally non-linear yet sensical flow, Douglas recollects the Faun. I wasn’t pretending to be the Faun, I was becoming it.27 The memoirs are punctuated by images taken by Douglas, but credited to dogbird in the appendix. Returning to the bestial. The animal moves like water in water, says Bataille.28 Fluid, seamless, seemingly without effort. The hawk surfs the sky as a fish runs downstream.

The scale of human to animal/machine is inverted – fencepost is giant

A Hawk ECU watches from the backdrop

And the dancer becomes prey

Sheep-farmer

DANIEL 29

Staff-shepherd (crook/ed)

BO PEEP

[[tin dog

on the backdrop with\/inverted\/gamma

URL blue ///////

where does a sound end

We must disregard “reproductive quests for perfect restoration”—and look at what is left, what is outside of the frame: “…a wild text,” says Halberstam, “a text that must remain unknown, unperformable, illegitimate, beyond classification—it exists instead as a legend, a phantasm, a performance that, like so many queer ephemeral acts and performances, can never be repeated.”29 Working with the slippages and confusions in these systems of difference and resisting tidy categorization, my dance through lost and living archives is a reproductive quest—to create linkages where they are missing, to trace bodies where they once lay, stood, moved, mourned, keened—and are still keening. This is a kind of illogical, feral surrogacy: itself a non-”normative” reproductive process, a bearing and a birthing. Recognize the “almost paralyzing fear” invoked by the stiff shell of the archive, the actual materials shoved off to the side, to return to the sound of the body and its muster of ghosts.30

tractor sounds are drawn out, repeated into drones

snippets of refrain / creaks

&Clean white light

Many limbed beings move together

Cries like bansheebirds become barks become whines

The fence post turns

90 degrees into a McCahon I

Strung up

Hamstrung

Crux

Photography by Stephen A'Court of Inland, performed by Douglas Wright Dance on 6 March 2002 at The Opera House, Wellington. Used by permission.

Ngā mihi nui ki a koe: Megan Adams & Ann Dewey; SOUNZ Centre for New Zealand Music; Tracey Slaughter; Karen Barbour; Lisa Perrott; Stephen A'Court; Auckland Libraries Special Collections.

Notes

1

Douglas Wright, Inland (2002), performed by the Douglas Wright Dance Company, with music composed by Juliet Palmer and performed with Deborah White (violin) at the Aotea Centre, The Edge, Auckland on 7 March 2002 [accessed 20 April 2023].

2

Drew Daniel, ‘All sound is queer’, in The WIRE, Issue 333 (2011).

3

Marie Thompson, ‘Sounding the Arcane: Contemporary Music, Gender and Reproduction’, in Contemporary Music Review, 39.2 (2020), 273–292 https://doi.org/10.1080/07494467.2020.1806630 (p.274).

4

Douglas Wright, ghost dance, (Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland: Penguin New Zealand), 2004, p158.

5

While definitions of queer are appropriately diverse, contested, and dynamic, for the purposes of this discrete piece of writing “queer” refers to and invokes any/every body, relationship, and way of being (for queer is both noun and verb) that exists outside the bonds of the heteronormative. Relationship here is used expansively, including relationality between/with humans as well as with animals, machines and more-than-human agents.

6

Jack Halberstam, The Queer Art of Failure (Durham: Duke University Press, 2011), p.73; Mel Y. Chen, Animacies: Biopolitics, Racial Mattering and Queer Affect (Durham: Duke University Press, 2012), p.67.

7

Halberstam, The Queer Art of Failure, p.89.

8

Halberstam, The Queer Art of Failure, p.106.

9

José Esteban Muñoz, Disidentifications: Queers of Colour and the Performance of Politics (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1999), p.31.

10

E. Patrick Johnson, ‘‘‘Quare’’ Studies, or (Almost) Everything I Know about Queer Studies I Learned from My Grandmother’, in Black Queer Studies: A Critical Anthology, ed. by E. Patrick Johnson and Mae G. Henderson (New York: Duke University Press, 2005), pp.124-158 (p.125) <https://doi-org.ezproxy.waikato.ac.nz/10.1515/9780822387220-009> [Accessed 12 May 2022].

11

Chen, p.85.

12

Halberstam, Wild Things: The disorder of desire (Durham: Duke University Press, 2020), p.41.

13

Douglas Wright, ghost dance, p.158.

14

Annie Potts, Philip Armstrong, Deidre Brown, The New Zealand Book of Beasts: Animals in our culture, history and everyday life (Auckland: Auckland University Press, 2013), p.4.

15

Nicole Shukin, Animal Capital: Rendering Life in Biopolitical Times (University of Minnesota Press, 2009), p. 45.

16

Shukin, p.87.

17

‘Glimpses of the frozen industry in Southland New Zealand’, (1939), Ngā Taonga Sound & Vision, Film and Video Collection: F36249 < https://www.ngataonga.org.nz/search-use-collection/search/F36249/> [accessed 2 December 2021]

18

Marika Cifor, ‘Stains and Remains: Liveliness, Materiality, and the Archival Lives of Queer Bodies’, Australian Feminist Studies, 32.91-92 (2017), 5-21 <10.1080/08164649.2017.1357014> (p.8).

19

Russell, Catherine, ‘Archiveology.’ In ‘Lexicon 20th Century A.D. Vol. 1 of 2’, ed. by Christine Davis, Ken Allan and Lang Baker, Public 19 (2000), p.22.

20

Russell, p.45.

21

Cifor, p.7.

22

Natalie Robertson, ‘Activating Photographic Mana Rangatiratanga Through Kōrero’, in Animism in Art and Performance, ed. by Christopher Braddock (Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017), pp. 45-65), p.47.

23

Robertson, p.61.

24

Russell, p.16

25

Mark Fisher, ‘The Metaphysics of Crackle: Afrofuturism and Hauntology’, Dancecult: Journal of Electronic Dance Music Culture, 5.2 (2013), 42-55 <10.12801/1947-5403.2013.05.02.03> (p.48).

26

Fisher, ‘The Metaphysics of Crackle: Afrofuturism and Hauntology’, p.49 (emphasis mine).

27

Douglas Wright, ghost dance, p.105.

28

Georges Bataille, Theory of Religion (NY: Zone Books, 1989), p.25.

29

Halberstam, Wild Things, p.55.

30

Bhanu Kapil, ‘Archive Fever’ in ‘The Vortex of Formidable Sparkles’, 1 February 2012, archiving a post from her now defunct blog ‘Was Jack Kerouac a Punjabi?’ <https://thesparklyblogofbhanukapil.blogspot.com/ 2012/ 02/archive-fever.html> (accessed 8 October 2018). Accessed in Sarah Howe, ‘Library of Opaque Memory: Spectral Archives in Brandon Som, Mai Der Vang and Bhanu Kapil’, in The Contemporary Poetry Archive: Essays and Interventions, ed. by Linda Anderson, Mark Byers and Ahren Warner (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2019), pp. 136-138.

Frances Libeau is a writer and artist from Tāmaki Makaurau. Their sonic compositions, sound designs, and writing feature across diverse platforms of music, art, film and theatre. Libeau’s work often explores material and semantic possibilities of queering compositional and archival practices. Libeau is a PhD candidate at the University of Waikato.